Today we bring you an article by Jack Scruby from the year 1959. We learn about Formation trays and a Regimental type game. I find this article interesting in that its contents closely mirrors a Napoleonic project that I have been working on for some time. Will I ever finish the project? Who knows? I am a very slow painter and in 30mm I’m even slower, so we shall see.

Also mentioned in this piece are the actual rules used to play the game. I may have a copy of these and if I do, I will post them in the near future. If you happen to have a copy, please let me know (just in case I can’t find a copy here).

ORGANIZING A NAPOLEONIC WAR GAME ARMY

by Jack Scruby

The War Game Digest Book III Volume II, June 1959

Any war gamer setting out to organize a Napoleonic war game army has several things to consider. But the basic elements should be scale and numbers. In the past few years I’ve made two complete Napoleonic armies; one in 54mm scale and one in 30mm scale; and perhaps my experience will be of some help to those of you interested in this period of miniature warfare.

Scale of the figures (i.e, their actual size) is of great importance, and one that takes careful consideration. Those players who like their figures painted as recognizable individuals will prefer the 54mm I’m sure. But the big drawback to this scale model is that they are expensive to buy or reproduce, they are bulky and hard to store, are difficult to painting quantity, and require large battlegrounds to maneuver on.

Several years ago I commenced making 30mm soldiers, and the glamor of the 54mm size figure was lost for good, and now my Napoleonic army in this scale that I spent a couple of years in the making, lies idly on my shelves gathering dust and cobwebs.

For I’ve found the 30mm scale is not too small, nor too large; its easily stored between battles, the figures are painted quickly, and enough “individualism” remains to satisfy my needs. Unlike our friend Ed Saunders, who is now specializing in soldiers that stand only 5/8 of an inch high, I’ll still stick to the 30mm figure, since no matter how small the figure, or how great the playing area, a miniature battle generally is fought on a small part of the playing field as each general is forced to concentrate his troops against his opponents concentrations.

The number of troops needed for Napoleonic war games can be decided by the area of playing space available, the amount of money available to buy soldiers with, and the time generally available to play the war game in. These factors should be combined, for upon each of them depends the number of troops one should have to fit his own particular needs and physical war game setup. Perhaps by telling you of my own war game armies, it will give you a “scale” to compare your own plans and ideas.

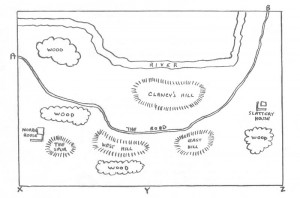

At the present time my 30mm Napoleonic armies consist of some 400 French and 400 British infantry figures, and l00 each of cavalry. I seldom use these many men to fight a war game with, but I have used this number in some games and did not find my 8 ft by 6 ft sand table too crowded.

Normally my opponent and I used armies composed of 260 infantrymen, 3 cannons and 50 cavalry (or less). To me this is about the right numbers — any less and its only a skirmish, any more and its crowded. Using this many men, battles normally will last from 5 to 7 hours duration.

Within recent months however, we’ve developed a new type of Napoleonic war game, based on ideas presented to us by John Schuster and Ted Haskell – We call this the Regimental Napoleonic war game, and in using these rules, organization of your troops is of prime importance.

Basically, under these rules, all infantry is formed into ‘Regiments’ of 20-men, and are mounted on a balsa wood moving tray (also called Formation Tray). All fighting is done on a ‘regimental’ basis; i.e. volleys are fired by a regiment, not by an individual count of men. When casualties within a regiment reach 3/4 of the original strength, that regiment is removed from the table. Up to that time, the regiment retains its full firepower.

Since we have been using these Formation Trays, we have found that more troops could be used, and moved, than possible in our previous battles. For naturally, it is as quick to move a tray containing 20 soldiers as it once was to move a single model soldier. Cutting down on the “movement time” has speeded up the game tremendously – once it would take at least fifteen minutes to move your entire force; now its only a few minutes.

Now, provided that you would use these Moving Trays, organization of your armies then basically depend on the number of Regiments. (One officer is usually added to each regiment, but is not counted in the volley – his biggest asset is that he counts as 2 points in a melee). Thus, if you decided to have lO man regiments per moving tray, you could easily have lO regiments – or – lOO men per side. In proportion you’d need 25 cavalry and one or two cannons. As you decide, you can then build up your armies further by adding more regiments, or by adding more men to your present regiments. Thus, in the end, your two opposing forces will balance out nicely.

As you get further into the war game, you’ll want some variance from having two equal forces always oppose each other. Some regiments can be “reinforced regiments”, and can have, say, l5 men instead of the basic lO men (as outlined above). Some can be Light Infantry regiments, or Guard regiments with more movement or firepower. And the Regimental Rules allow for more – or less -firepower depending on the formation (In Line, Column, or Square) the regiment happens to be in at the time of delivering the volley. So there are many ways to “relieve the organizational monotony” of a basic infantry regiment mounted on a moving tray.

Cavalry, artillery and gun crews, are not mounted on trays, but are moved as individuals. Often too, when individual regiments are cut down by casualties, we “dismount” the figures from the trays and move them (in formation) individually until the Regiment is depleted and removed from the table. But, taking an army as I outlined that we use — 260 infantry, 50 cavalry, 3 guns – each player on any given move has only 13 formation trays to move, 5O cavalry and the 3 guns and crews – a matter of only a few minutes time! Our average war game has been cut down at least two hours just by the introduction of these moving trays.

One thing too I like about these trays (aside from their “organizational value”) is the fact that between battles, the 30mm troops really look sharp when set up on their storage shelves. We generally place the casualties back on the trays whenever a regiment is removed from the table and when you set it upon your shelf it makes a nice showpiece to show your friends.

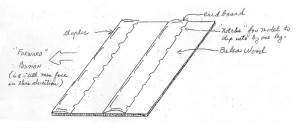

These Formation trays are quite simple to make. I use pieces of 3 inch by 1/4 inch balsa wood, cut to-the appropriate length. Since I mount a 2O man regiment in two rows (lO men to a row) this is generally about 7 inches long by 3 inches wide . When the tray is moved into Line Formation, the lO men face forward. In Column formation, it forms two lines of marching men. (They naturally are not moved on the tray – only – the tray is moved to denote whether in Line or Column. When a “SQUARE ” is formed, we merely place a card on the tray, thus denoting that this tray is formed in Square)

In order to hold the figures onto the-tray, there are two simple ways of doing it. If you use the floor or a hard table top to fight on, you need merely coat the balsa wood tray with a thin layer of childs clay. The soldiers stick fine to this, and are easily removed. You don’t need to even color the tray if you use the vari-colored clays usually sold in a box.

If you play on a sand table like T do, the clay of course cannot be used. It is simple however to make the tray by merely cutting out strips of cardboard, notching tMorhem to fit the leg of the soldier, and stapling these cardboards to the balsa wood. Spray the tray brown, green or gray, and you‘re in business. You’ll find that even on the steepest terrain (on a dirt table) the soldiers will stay inside the formation tray without too much

toppling over.

Thanks to John Schuster – who took the time to stencil out the Regimental Rules — a limited number of copies of these rules are available, Those readers who have not already received them from me, should write, and I‘ll send them the rules – as long as they last.

Whether this idea of Moving Trays can be worked for other types of Musket Period war games – such as the Civil War, American Revolution, etc. – I cant say. For the Napoleonic games, where Regiments fought shoulder to shoulder, it brings an added realism that is not possible any other way, it also eliminates the players from using “modern” tactics of straggling and well spread out lines, and forces them to fight the battles as they were fought in that day and age.

Thus, you’ll find the Moving Tray type of game makes for much easier organization of armies, cuts down the playing time, allows more~troops to be used, relieves the dullness of fighting a slow moving opponent, and in general adds to the overall appearance of the battlefield of Napoleonic war games.

More soon…